Comments on Bach's notation in the French style

Written on December 24th, 2022 by Ruoshi SunDisclaimer: The following represents my personal opinion only.

In this essay I examine two examples regarding Bach’s notation in the French style and present my interpretation.

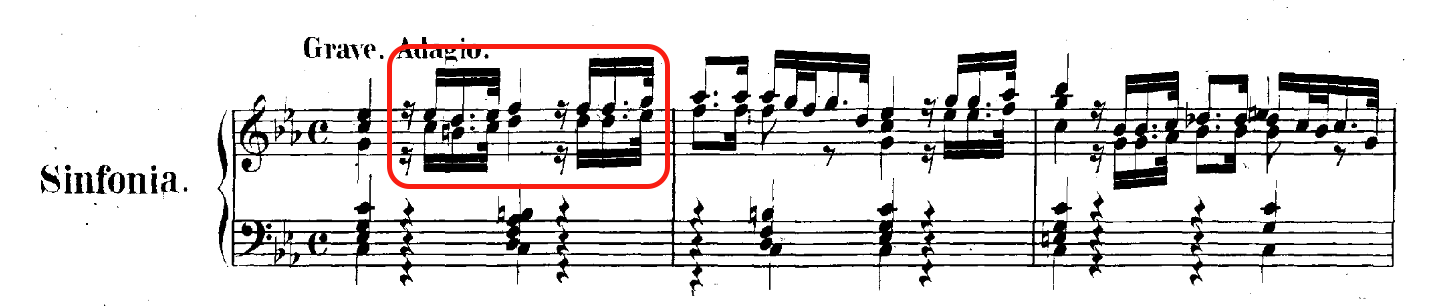

Example 1: Sinfonia from Partita No. 2 in C minor, BWV 826

The first two occurrences of the rhythmic motif at question are marked. This occurs throughout the Grave section. In András Schiff’s interpretation, however, the 16th rest is (double-)dotted, as he explains in his lecture on the Bach Partitas.

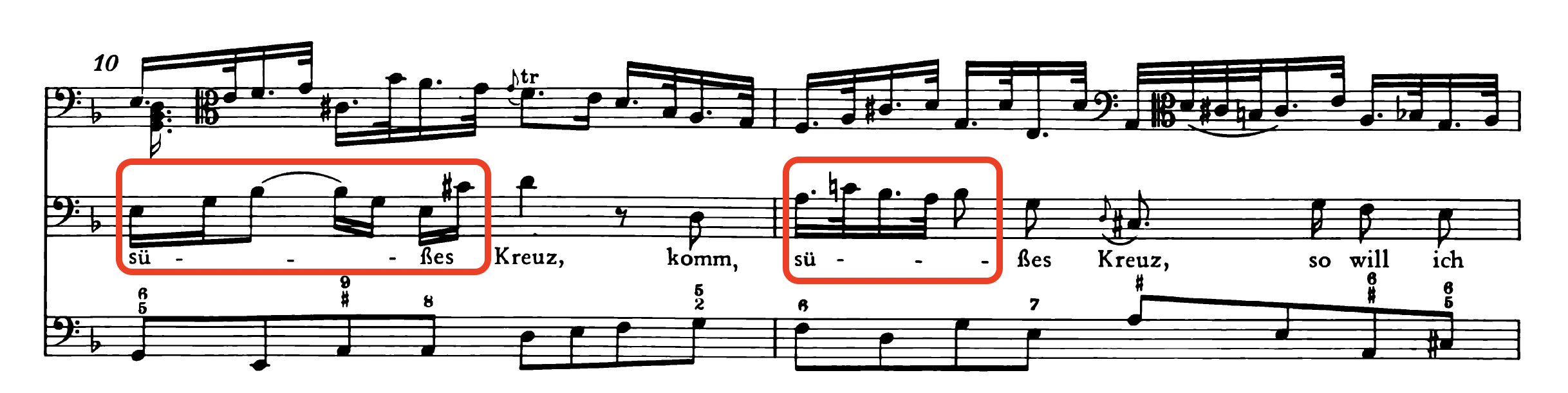

It is certainly a very compelling interpretation. However, I would still choose to play it literally due to an observation of Bach’s “Komm, süßes Kreuz” from St. Matthew Passion, BWV 244. The prevalence of dotted rhythm suggests it is in the French style (compare with Contrapunctus II and VI from the Art of Fugue). The first occurrence of the rhythmic motif at question is marked.

Next, if we look a few bars ahead, we see that Bach uses both the undotted and dotted rhythms in the bass solo. One must also take into consideration that performers back then read from their parts, not the full score, so they did not know in advance whether the other parts were playing in dotted rhythms or not. Hence, I believe Bach was very precise about whether he intended a note to be dotted or not, and so the first 16th note in the previous figure should be played literally and not as a 32nd (or a 64th if double-dotted).

Next, if we look a few bars ahead, we see that Bach uses both the undotted and dotted rhythms in the bass solo. One must also take into consideration that performers back then read from their parts, not the full score, so they did not know in advance whether the other parts were playing in dotted rhythms or not. Hence, I believe Bach was very precise about whether he intended a note to be dotted or not, and so the first 16th note in the previous figure should be played literally and not as a 32nd (or a 64th if double-dotted).

Assuming that Bach was consistent with his notation, I would apply the same “literal” interpretation to the Partita. One could argue about single- versus double-dotted, but that is a different subject matter.

Example 2: Gigue from French Suite No. 1 in D minor, BWV 812

The rhythmic motif at question consists of a dotted 8th followed by three 32nd notes, which first appears in the fugue subject.

This example is especially problematic due to the context of “gigue.” There are three interpretations that I am aware of:

This example is especially problematic due to the context of “gigue.” There are three interpretations that I am aware of:

- Play the 32nd notes literally. Example: Glenn Gould. (I am in favor of this interpretation.)

- Play the 32nd notes as triplets. The 2017 Henle edition suggests that this “is conceivable.”

- One school argues that gigues are in three or compound time and thus it would be wrong to play this movement literally. Instead, one should play in 12/8 meter and adjust all the note values accordingly. Example: András Schiff.

I do not claim to be a scholar in Baroque dance music, but I wish to share some of my observations on the rhythmic motif alone. As with the first example, I examine Bach’s corpus for evidence. This rhythmic motif occurs in two preludes from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, namely F-sharp major and A-flat major. The former uses the ambiguous dotted notation:

and the latter uses the precise notation:

and the latter uses the precise notation:

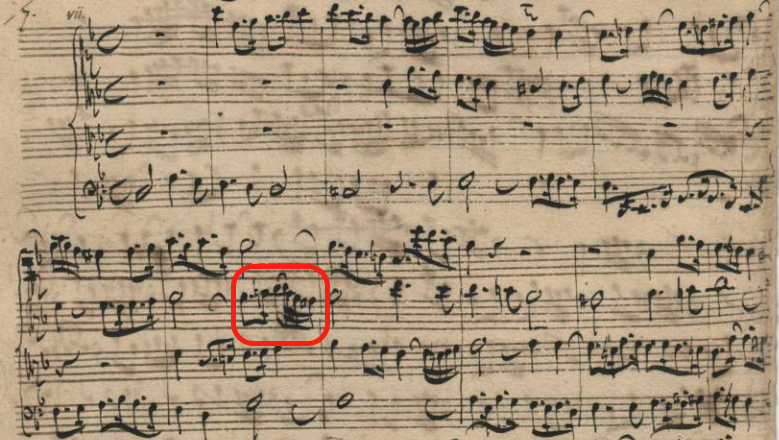

The precise notation is also used in Contrapunctus VI from the Art of Fugue, BWV 1080:

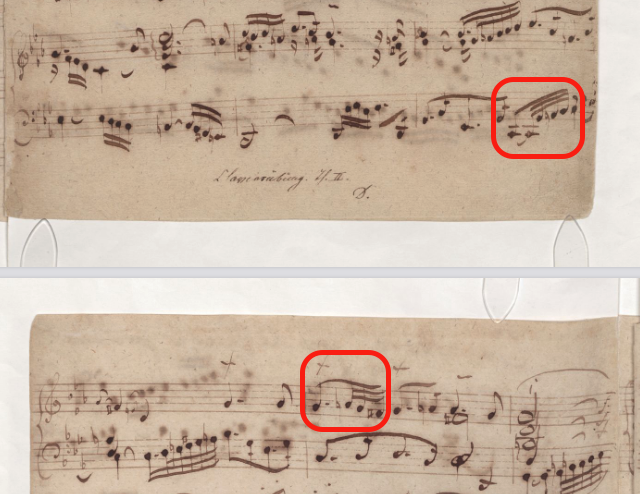

I believe the equivalence of the two notations can be established in Bach’s manuscript of the French Overture, BWV 831. Here both notations are used. In the first marked instance, we see the precise notation; in the second instance, the second 32nd note is aligned with the 16th note in the left hand:

It would not make sense to play the two notations differently. In other words, then, the dotted notation should be treated exactly as the precise notation. The dotted notation could be only a matter of convenience in writing, which should not have been a source of confusion at the time.

In light of such supporting evidence, I disagree with the 2nd interpretation (triplets), and, assuming Bach’s notation were consistent across compositions, the same rhythm should be played in the Gigue, implying the meter is indeed in 2/2 (or 4/4 in certain editions). I am not convinced that Bach would deliberately compose in a wrong meter.